- The Handbasket

- Posts

- Crackdown

Crackdown

Writing through history and heartbreak.

If you want to support The Handbasket’s 100% independent journalism, subscribe for free now. You can also become a premium subscriber or leave a tip.

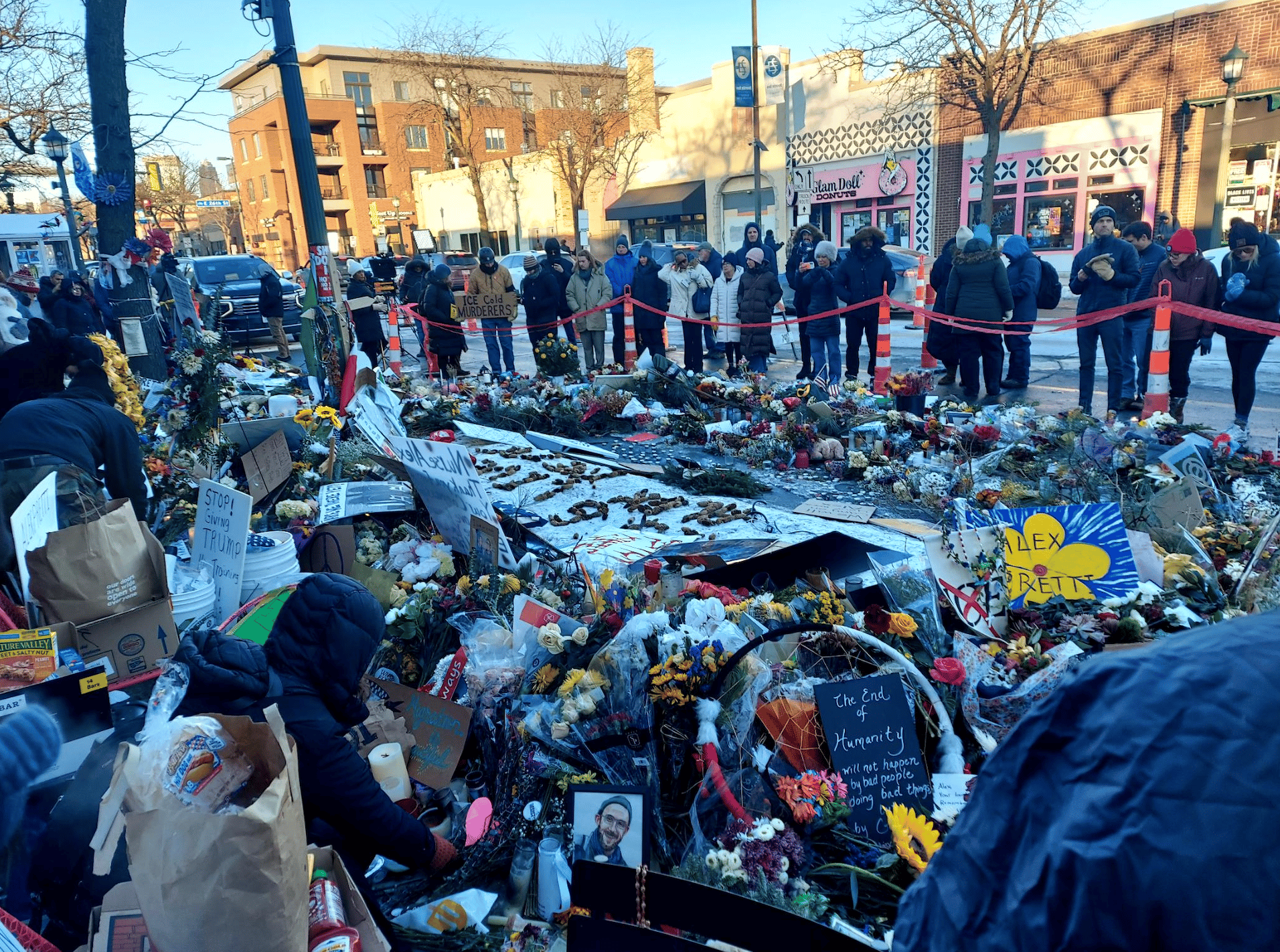

Memorial for Alex Pretti where he was killed. (Shared with The Handbasket by source who wishes to remain anonymous.)

Since Renée Good was murdered on January 7th, the national mood had been funereal. We watched a mother, a wife, a poet, a friend be executed, our insides hollowed out as we watched her be chased by bullets while she tried to drive away. It was hard to imagine anything more gutting. Then I saw Wael and Maher Tarabishi’s story.

Wael was also killed by the state, in a different but no less cruel way. ICE took Maher, his father and primary caregiver, back in October and allowed Wael, a 30-year old with Pompe disease, to die slowly from lack of proper care—or maybe from a broken heart. He entered the hospital in late December and never left alive. Meanwhile his father, his closest companion, remained locked away, helpless without the ability to be physically present for his son. His family is now trying to get him humanitarian release for Wael’s funeral, but ICE isn’t known for its humanitarianism. It’s the kind of story that makes you believe there is no God.

I sobbed and sobbed after reading Wael and Maher’s story, hoping the tears could somehow flush out the unbearable sadness from my body; ease the joints that had gone stiff from tensing, and restore even a modicum of hope that there was still good somewhere. Alex Pretti’s mortal sacrifice was, in a way, that hope.

When video began circulating Saturday morning of federal agents brutalizing and shooting a man in Minneapolis, it felt shocking but also inevitable. After Renee Good’s murder two and a half weeks earlier, the federal government did everything it possibly could to excuse it, using the thinnest justifications that feeling people saw right through and to which hardened hearts clung. She was, after all, a “fucking bitch” as the agent who shot her muttered moments later. She was an expendable woman in the eyes of people who, when you really get down to it, see all women as expendable. Perhaps there was a part Alex Pretti—a cisgender, heterosexual white man—that knew in the eyes of the state, his life meant more. And so he stepped forward to help a woman under attack by CBP agents, knowing very well he could be killed for it.

It wasn’t the first time Alex Pretti had put himself in harm’s way. CNN reported Tuesday “that about a week before his death, he suffered a broken rib when a group of federal officers tackled him while he was protesting their attempt to detain other individuals.” Despite his injury, he came back.

The people of Minnesota, the rest of the country has learned these past few weeks, just keep coming back. Their relentlessness offers a blueprint for how to react when ICE inevitably arrives somewhere new to stir up trouble where there was none; how to look violence dead in the eye and say not in my town; how to provide aid laterally when you know those at the top won’t be passing any down.

Headlines call it a “crackdown” on immigration and a “clash” between the government and “protesters,” when in reality it’s murderous occupying forces being confronted by people who just want to live free of their violence. While Greg Bovino has reportedly left town, the terror plays on and the need for neighbors to protect neighbors continues apace.

Earlier this month I called a man in Minneapolis we’ll say is named James. The line rang a few times with no response, and a few minutes later he called back to explain: He’d been responding to an ICE sighting nearby that had been flagged in a local group chat. James is just a guy. He lives in Minnesota with his family and pays taxes there and has had a generally nice life. But now while working his remote job from home, he runs out at a moment’s notice to protect his neighbors from federal mercenaries. Because that’s what good neighbors do.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the contrast between the unfathomable violence being inflicted by the federal government and the mundane tasks of everyday life. One minute you’re putting the same fork in the dishwasher for the 800th time, the next you’re taking down plate numbers for an SUV with heavily-tinted windows; or in Renee Good and Alex Pretti’s cases, being shot and killed. Renee Good and her wife had just dropped off her six-year-old son at school when she came face-to-face with ICE; despite the unimaginable loss, her wife would still need to pick him up later.

While the stories of American citizens being harmed by the lawless agencies of DHS seem to be resonating most widely, this is, at its core, about immigrants and immigration. Masked men trawl our streets in search of people who have black or brown skin, who primarily speak a language that isn’t English, plucking them off the street to disappear into the vast bureaucracy of the federal detention system. They’re reduced to an A-Number, a nine-digit identifier from DHS used to track an individual’s movement through the system. The A stands for alien.

Non-citizens caught in DHS’s web of terror don’t get the hero treatment because we don’t know most of their names. They’ve been forced to live in the shadows since Trump declared open season on their lives. While Good and Pretti may inspire us to keep going and to use any privilege we have to stand between the hunters and the hunted, the unnamed and unseen are the ones we’re visibly fighting for. It is because we believe they belong here, that they have legal and human rights, that they deserve to be here just as much as we do that we have this fight at all. And on the rare occasions we do know their names—Wael. Maher. Liam.—we have to shout their stories so loud that it’s impossible for the enemy not to hear.

One year ago yesterday, I published the story that changed my career and was one of the earliest signs that Trump’s second administration was gunning for total destruction. The White House Office of Management and Budget sent a memo to the heads of executive departments and agencies letting them know there would be an imminent “pause” on all federal grants and loans so they could do an audit making sure each they were in compliance with Trump’s hateful values. I was the first one to obtain and publish a copy, and I signed off my piece by writing “One week down. Many to go. Let’s do this, y’all.” It’s hard to believe we made it another 52 weeks. And it’s hard to believe how much the government has been dismantled and how many human rights have been destroyed in that period of time.

I keep searching for a way to sum it all up, to explain to my future self and other’s future selves what it was like living through history. But even for someone like me who has not directly been in harm's way, there are maddeningly few words that feel powerful enough to even describe the experience of simply bearing witness from afar. It feels almost hubristic to think I, or anyone, could possibly capture the current essence of existence.

The enormity of everything feels too monstrous to tackle and words about facts and figures seem locked behind a door. I so badly want to adequately express how it is to be a journalist right now, how it is to simply be a person in this country right now, and sit with the frustration of knowing I can’t. But it’s better to try than risk forgetting. This isn’t the time to say nothing.

Reply